Illustrated by WILLER

Illustrated by WILLERThe Project Gutenberg EBook of Martians Never Die, by Lucius Daniel This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Martians Never Die Author: Lucius Daniel Illustrator: Ed Emshwiller Release Date: August 19, 2009 [EBook #29735] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MARTIANS NEVER DIE *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Stephen Blundell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

It was a wonderful bodyguard: no bark, no bite, no sting ... just conversion of the enemy!

At three-fifteen, a young man walked into the circular brick building and took a flattened package of cigarettes from his shirt pocket.

"Mr. Stern?" he asked, throwing away the empty package.

Stern looked with hard eyes at the youthful reporter. He recognized the type.

"So they're sending around cubs now," he said.

"I'm no cub—I've been on the paper a whole year," the reporter protested, and then stopped, realizing his annoyance had betrayed him.

"Only a year. The first time they sent their best man."

"This ain't the first time," said the young man, assuming a bored look. "It's the fourth time, and next year I don't think anybody will come at all. Why should they?"

"Why, because they might be able to make it," Beryl spoke up. "Something must have happened before."

Stern watched the reporter drink in Beryl's loveliness.

"Well, Mrs. Curtis," the young man said, "everyone has it figured out that Dr. Curtis got stuck in the fourth dimension, or else lost, or died, maybe. Even Einstein can't work out the stellar currents your husband was depending on."

"It's very simple," replied Beryl, "but I can't explain it intelligibly. I wish you could have talked to Dr. Curtis."

"Why is it that we have to come out here just once a year to wait for him? Is that how the fourth dimension works?"

"It's the only time when the stellar currents permit the trip back to Earth. And it's not the fourth dimension! Clyde was always irritated when anyone would talk about his traveling to Mars in the fourth dimension."

"It's interdimensional," Stern put in.

"And you're his broker?" asked the reporter, throwing his cigarette down on the brick floor and stepping on it. "You're his old friend from college days, handled his financial affairs, and helped him raise enough money to build his machine?"

"Yes," Stern replied, a little pompously. "It was through my efforts that several wealthy men took an interest in the machine, so that Dr. Curtis did not have to bear the entire expense himself."

"Yeah, yeah," the reporter sighed. "I read an old story on it before I came here. Now I'm out of cigarettes." He looked hopefully at Stern.

Stern returned the look coldly. "There's a store where you can buy some about three blocks down the road."

"Is that the room where he's expected to materialize with his machine?" The reporter pointed to an inner door.

"Yes. Dr. Curtis wanted to be sure no one would be injured. This inner circular room was built first; then he had the outer wall put up as an added precaution. The circular passageway we're in leads all around the old room, but this doorway is the only entrance."

"And what are those holes in the top of the door for?"

"If he returns, we can tell by the displaced air rushing out. Then the door will open automatically."

"And when is the return scheduled for?" asked the reporter.

"Three-forty-seven and twenty-nine seconds."

"If it happens," the reporter added skeptically. "And if it doesn't, we have to wait another year."

"Optimum conditions occur just once a year."

"Well, I'm going out to get some cigarettes. I've got time ... and probably nothing to wait for. I'll return though."

He walked briskly through the outer door.

"This is the hardest part of the year, especially now. Suppose he did come back," Beryl said plaintively.

"You don't have to worry," Stern assured her. "Clyde himself said that if he didn't come back the second year, he might not make it at all." Stern opened his gold case now and offered Beryl a cigarette.

She shook her head. "But he made two trial runs in it first and came back."

"That was for a short distance only—that is, a short distance astronomically. Figuring for Mars was another story. Maybe he missed the planet and ..."

"Oh, don't! It's just not knowing that I can't stand."

"Well," he said drily, "we'll know in—" he stopped and looked at his wristwatch—"in just about fifteen minutes."

"I can't wait," she moaned.

He put his arm around her. "Relax. Take it easy and stop worrying. It'll just be like last time."

"Not the last time at all. We hadn't—"

"As soon as we are able to leave here," he said, drawing her close and squeezing her gently, "I'll take steps to have him declared legally dead. Then we'll get married."

"That's not much of a proposal," she smiled. "But I guess I'll have to accept you. You have Clyde's power of attorney."

"And we'll be rich. Richer than ever. I'll be able to use some of my own ideas about the investments. As a matter of fact, I have already." And he frowned slightly.

"We have enough," Beryl said quickly. "Don't try to speculate. You know how Clyde felt about that."

"But he spent so damned much on the machine. I had to make back those expenses somehow."

Steps sounded outside and they drew apart. The reporter came in with a companion of about his own age.

"Better wipe the lipstick off," he grinned. "It's almost time for something to happen."

Stern dabbed at his mouth angrily with his handkerchief.

At first the sound was so soft that it could hardly be heard, but soon a whistling grew until it became a threat to the eardrums. The reporters looked at each other with glad, excited eyes.

The whistling stopped abruptly and, slowly, the door opened. The reporters rushed in immediately.

Beryl gripped Stern's hand convulsively. "He's come back."

"Yes, but that mustn't change our plans, Beryl dear."

"But, Al ... Oh, why were we so foolish?"

"Not foolish, dear. Not at all foolish. Now we have to go in."

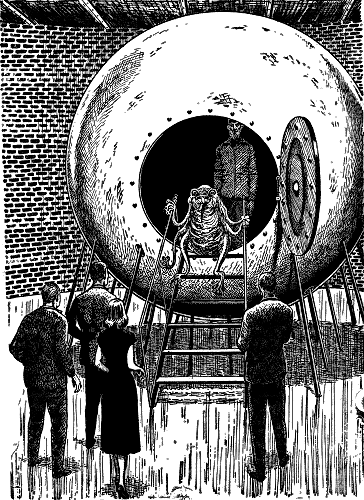

Inside the room was the large sphere of metalloy. It had lost its original gleam and was stained and battered, standing silent, closed, enigmatic.

"Where's the door?" called the first reporter.

The sphere rested on a number of metal stilts, reaching out from the lower hemisphere, which held it about three feet from the floor, like a great pincushion turned upside down.

Slowly, a round section of the sphere's wall swung outward and steps descended. As they touched the floor, both reporters, caught by the same idea, sprinted for it and fought to see which would climb it first.

"Wait!" shouted Stern.

The reporters stopped their scuffling and followed Stern's gaze.

Something old and leathery and horrible was emerging from the circular doorway. Several tentacles, like so many snakes, slid around the hand rail which ran down the steps. Then, at the top, it paused.

Stern felt an immediate and unreasoning hate for the thing, whatever it was, a hate so strong that he forgot to feel fear. It seemed to him to combine the repulsive qualities of a spider and a toad. The body, fat and repugnant, was covered by a loose skin, dull and leathery, and the fatness seemed to be pulled downward below the lower tentacles like an insect's body, until it was wider at the bottom than at the top.

Like a salt shaker, Stern thought.

It turned its head—it had no neck; the loose skin of the body just turned with it—and looked back inside the sphere. The head resembled a toad's, but a long trident tongue slid in and out quickly, changing the resemblance to that of a malformed snake.

From the interior, Dr. Curtis appeared beside the creature and stood there vaguely for a moment. Stern noticed that his clothes seemed just as new as when he had left, but he had grown a long, untrimmed beard, and his face had a vacant expression, as if he were hypnotized.

The creature looked upward at Curtis, who was head and shoulders taller, and its resemblance changed again in Stern's mind, so that now it looked like a dog, at least in attitude. From its mouth came a low hissing noise.

Illustrated by WILLER

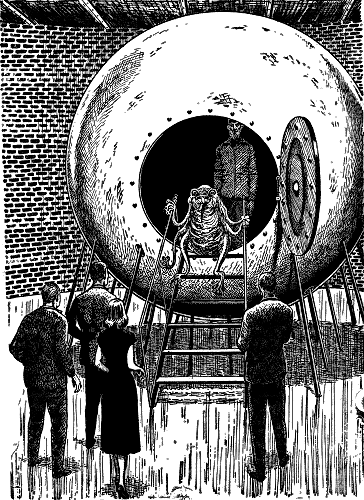

Illustrated by WILLERCurtis looked down at the dog-spider-toad, his eyes slowly beginning to focus. The creature wiggled like a seal with a fish in sight, then slid and bumped down the steps, with Curtis following him.

"Clyde!" cried Beryl and rushed toward Curtis.

The outstretched tentacles of the beast stopped her, but at a touch from Curtis they fell away and Beryl was in his arms.

Stern watched the scene sourly and with rage in his heart. Why hadn't Clyde waited another year? Then nothing could have changed things. Now he would lose not only Beryl, but the management of the money that was left, and the marketing of new patents on the machine. Curtis did not approve of speculation, especially when it lost money.

"You've changed, Clyde," Beryl was saying as she hugged him. "What is the matter—do you need a doctor?"

"No, I don't want a doctor, but I have to get home," said Curtis.

Stern felt anger again beating in his brain like heavy surf on a beach. Curtis was sick. The least he could have done was die. Well, maybe he still would. And if he didn't he could be helped to—Stern saw the beast looking at him intently, malevolently. Its face might have looked almost human, now that it was so close, if it had possessed eyebrows and hair. As it was, its nose rose abruptly and flared into two really enormous nostrils, but its mouth looked small and wrinkled, like that of an old grandmother without any teeth.

They turned to the doorway without noticing the absence of the reporters, who had long since run off to telephone and get photographers.

Curtis walked slowly. He would stop for a moment, look about as if expecting something entirely different, and then he would move forward again.

They all got into the car, Curtis and Beryl on the front seat, with Beryl driving, and Stern and the creature in the rear. As Beryl drove, Stern looked savagely at the back of Curtis's head, but he felt the beast staring at him balefully. Could it be a mind reader? That was ridiculous. How could anything that couldn't speak read a person's mind?

He turned to study it. The Martian, if that was what it was, had only six tentacles, three on each side. The lower ones were heavy and almost as thick as legs. The upper ones were small and were obviously used as hands, while it was possible that the middle ones could be used either way. A series of suction cups or sucking pads were at the end of each tentacle. With equipment like this, it could walk right up the side of a building, except, perhaps, for the higher gravity of Earth.

Stern could smell it now, a dry, desert smell, and that made it more revolting than ever. They were born to hate each other.

When they got home, Beryl was all solicitousness. The way a woman is when she has a man to impress, Stern thought.

"Just sit right here in your old chair," she told Curtis, "and I'll call a doctor. Then I'll put some water on to heat." But first she knelt by his side and laid her head on his breast. "Oh, darling," she said with a sob, "Why did you wait so long? I've missed you so."

A very good act, Stern told himself bitterly, without believing it at all.

She got up and turned toward Stern. "Will you help me get some water on, Al?" she asked. "I'm going to phone."

He went into the kitchen. He knew where the kettle was, the refrigerator, the mixings. He could hear her dialing, and then, before he got the kettle on the burner, she came inside and closed the kitchen door.

"Clyde's sick and I have to take care of him," she said anxiously.

It wasn't entirely the money, he confessed to himself now. He hated the situation, but he had to give in—on the surface anyway.

"Okay, let's forget the whole thing," he said.

"Oh, Al dear, I knew you'd understand! I've got to go back now and try the phone again. I got a busy signal."

Stern followed her, still rankling at the way Curtis had forced Beryl to live while he spent so generously on his own expensive interests. Shortly after their marriage, he had built a home for Beryl and himself in an exclusive suburb, on a hilly bit of land with a deep ravine at the back. But it was small and Beryl had not even been allowed maids except when they entertained, which was seldom. Soon he would change all that, Stern told himself. They had not dared to while Clyde was away.

In the modern living room, Curtis sprawled in his easy chair as though he hadn't moved since they had placed him there. But his air of abstraction seemed to have increased. Before him sat the beast, looking, Stern thought, more like a dog than ever. Its head wasn't cocked to one side, but that, less than its alien appearance, was the one thing to spoil the illusion.

Tires screeched in the driveway while Beryl was still at the telephone. Stern went to the front door, closed it and put the chain bolt in place. The back door would still be locked and they would hardly try to force the screen windows.

Heavy steps pounded up the front walk. "Did Dr. Curtis really get back?" The first man shot out. The one who followed had a camera.

"Dr. Curtis has returned," Stern spoke through the opening of the front door which the chain permitted, "but his physical condition won't permit questioning, at least until his doctor has seen him."

"Did he really bring back a Martian? We want to see the Martian anyway."

"We can't have Dr. Curtis disturbed in any way until after his physician has examined him," Stern said bluntly.

"Is he in there?"

"We'll give you a report when we're ready."

A second car pulled up to the house as Stern shut the front door, and went to check the rear one. When he came back, flashes from the window showed the cameraman was trying to take pictures through the glass. Stern drew the shades.

"Well, poor Schaughtowl, so you had to come with me," Curtis was saying to the monster.

The beast wiggled again as it had on the steps of the machine. A tail to wag wasn't really necessary, Stern decided, when there was so much body to wiggle.

Schaughtowl, as Curtis addressed it, seemed to brighten in the darkened room.

"Poor, dear Schaughtowl," said Curtis gently.

It was unmistakable now—the skin actually brightened and emitted a sort of eerie, luminous glow.

Curtis leaned over and put his hand on what would have been Schaughtowl's neck. The loose skin writhed joyously, and, snakelike, the whole body responded in rippling waves of emotion.

"Gull Lup," the monster—said wasn't the right word, but it was not a bark, growl, mew, cheep, squawk or snarl. Gulp was as close as Stern could come, a dry and almost painful gulping noise that expressed devotion in some totally foreign way that Stern found revolting.

He realized that the phone had been ringing for some time. He disconnected it, and then heard loud knocking.

"It's Dr. Anderson," he heard a man's voice calling impatiently and angrily.

Cautiously, Stern opened the door, but his care was needless. With a few testy remarks, the doctor quickly cleared a space about the door and entered.

He went at once to Curtis, with only a single shocked glance at Schaughtowl.

"Where the devil have you been and where in hell did you get that thing?" he asked as he unbuttoned Curtis's coat and shirt.

Since playing with his pet, Curtis seemed more awake. "I went to Mars," he said. "They're incredibly advanced in ways we hardly guess. We're entirely off the track. I just came back to explain how."

"Your friend doesn't look very intelligent," the doctor answered, busy with his stethoscope.

"Animals like Schaughtowl are used for steeds or pets," said Curtis. "The Ladonai are pretty much like mankind, only smaller."

"Why did you stay so long?"

"After I left, the Ladonai told me, they were going to shut off any possible communication with Earth until we advance more. They think we're at a very dangerous animal-like stage of development. Once I came home, I knew I couldn't go back, so I wanted to learn as much as I could before I left them."

"Stand up for a minute," ordered the doctor.

"Not right now," said Curtis. "I'm too tired."

"You'd better get to bed, then."

"I think not. It's merely caused by the difference in gravity and heavier air. The Ladonai told me to expect it, but not to lie down. After a while I'll try to take a short walk."

So Clyde wasn't going to die, after all, Stern thought. He had come home with a message, and, remembering the determination of the man, Stern knew he wouldn't die until he had given it. But he had to die. He would die, and who was competent enough to know that it wasn't from the shock of having come home to denser air and a heavier gravity?

There were ways—an oxygen tube, for example. Pure oxygen to be inhaled in his sleep by lungs accustomed to a rarified atmosphere, or stimulants in his food so it would look like a little too much exertion on a heart already overtaxed. There were ways.

Stern's scalp tingled unpleasantly, and he saw the Martian looking at him intently, coldly. In that moment Stern knew without question that his mind was being read. Not his idea, perhaps, but his intent toward Curtis. The Martian would have to be attended to first.

"Is it true, Dr. Anderson? Will he be all right?" Beryl was sitting on the arm of the chair next to Schaughtowl, and she was looking at Clyde almost as adoringly as the Martian. A few hours had undone all that Stern had managed to do in four years.

If Stern had been uncertain, that alone would have decided him.

"I think so," said the doctor. "He seems to be uncomfortable, rather than in pain. I'll send you a prescription for his heart, if he breathes too heavily. Be sure, though, not to give him more than one pill in three hours."

"Of course." Beryl was never that solicitous toward Stern.

"And you'll be in quarantine here until the government decides what, if any, diseases he and the Martian may have brought back with them."

"None at all, Doctor." Curtis's voice was markedly more slurred, and he stared intently with unblinking eyes at the blank wall.

"Well, that's something we can't tell yet. Well have to keep out the press and television men, anyway, because of your health. If I'm not detained, I'll be back tomorrow morning. Call me if there's any change."

On his way out, the physician was besieged by reporters and photographers, baulked of better subjects. Shortly after the doctor's departure, police sirens came screaming up. The men waiting around the house were moved outside the gate and a guard was set at every entrance.

Later, a messenger came, was interrogated by the police sergeant who took a small package from him and brought it to the house.

"Medicine," the sergeant said, handing it gingerly to Stern. "You can't leave here without permission." And he walked hurriedly away.

This might be the answer. Stern had a good idea of what the doctor had prescribed—something he'd said, for the heart. It must have been pretty powerful, too, for the doctor to warn against an overdose. Two at once might do it, or another two a little later.

But there was Schaughtowl.

"Al," said Beryl, "stay with Clyde while I fix something for him to eat."

She was more beautiful than ever. Emotions, he thought wryly, become a woman; they thrive on them. In a few minutes a woman could change like this. It was enough to make a man lose faith in the sex.

"Certainly," he said easily.

Curtis seemed to sleep with wide open eyes gazing blankly at the far wall. Schaughtowl sat motionless before him, watchful as a dog, yet still like a snake or spider patiently waiting. Didn't the beast ever sleep?

A drink was what Stern needed. He went to the closet and poured a double brandy. He sipped it slowly. As delicious fire ran down his gullet and warmed his stomach, he felt his tension ease and a sense of confidence pervade his mind.

He needn't worry. He was always successful, except that once with the stocks. And he had calm nerves.

There were guards out in front now in khaki uniform; the Governor must have called out a company of the National Guard. Stern noticed some state police, too. The house was well guarded on the three sides surrounded by a neat, white picket fence. In the back, the severe drop into the ravine made guards there unnecessary.

It was dark before Dr. Curtis moved. Beryl was watching him; she had little to say to Stern now.

"How about some broth, dear?" she asked Curtis immediately.

Slowly, Clyde's eyes focused on her. He smiled. "Let's try it."

He let Beryl feed him, sitting on a stool beside his chair and being unnecessarily motherly and coddling about it.

For a while after he had eaten, Clyde sat in his chair, looking at Beryl with his new and oddly gentle smile. It seemed to activate some hidden response in her, for she glowed with tenderness.

"I suppose," Curtis slurred, "I ought to try to walk now."

"Let me help." Stern rose and crossed the room.

The Martian rustled like snakes in the weeds, and hissed.

Beryl said without suspicion, "Thank you, Al. I knew you'd do whatever you could for Clyde." And she rested her hand trustingly on his arm.

What was past was past, not to be wept over, not to be regretted.

"Like to walk out in the back for the air?" Stern asked. "The breeze is coming from that direction."

"That will do very well," said Curtis, obviously not caring a bit.

Stern helped Curtis from his chair and supported him under the arm. They went out the back door, the Martian slithering after them. It was cooler in the garden. Stern felt a renewed surge of self-confidence.

"The stars—" Curtis stopped to look upward.

The night was almost cloudless and there was no moon. The house hid any view of the crowds and the guards holding them back. They were alone in the dark.

Curtis started forward again, with the Martian scraping along behind. It would never let Curtis out of its sight as long as it lived; that much was clear to Stern.

He guided Curtis to a seat close to the ravine, a favorite spot. Always the Martian was a step—or a slither—behind, and when Curtis sat down, Schaughtowl sat between his beloved master and the precipitous drop.

Stern picked up a rock from the rock garden and tossed it into the ravine. The Martian did not take his eyes off Curtis. Stern picked up a larger rock, a sharp, pointed one. He was behind the Martian and Curtis was looking away unseeingly into the night.

It was simple, really, and well executed. The beast's skull bashed in easily, being merely thin bones for a thin atmosphere and light gravitation. A push sent it over the edge of the ravine.

Curtis sat unnoticing, and the traffic jam out front created more than enough confusion to drown out any noise from the creature's fall.

Stern's palm stung. He realized that, before the Martian had pitched over the ravine, a suction pad had for a moment caught at his hand. It had done the beast no good, though.

Curiously, the Martian had not guarded itself, only Curtis. Sitting with its back to Stern had really invited attack. The mind-reading ability was just something that Stern had nervously imagined.

The police would not be able to tell his rock from any other. The heavy body, its ungainly movement and thin bones would explain everything. Besides, there was no motive for killing the Martian and what penalty could there be? It couldn't be called murder.

Stern looked at the palm of his right hand, the one that had held the rock. It stung a little, but in the darkness he couldn't see it. A stinger of some kind, like a bee, probably. The hell with it—couldn't be fatal or Curtis would have warned them about it.

The Martian had been walking by the ravine and had clumsily fallen in. He would report it after he had got Curtis back into the house.

Curtis was easy to arouse and didn't seem to miss Schaughtowl. Stern maneuvered him to the living room, where he sank into a chair and fell into his mood of abstraction.

Beryl must be in the kitchen cleaning up, Stern supposed. Perhaps he had better put some kind of germicide on his palm, just to ward off infection.

He looked at Curtis relaxed in the chair. Clyde suddenly appeared oddly boyish to him, hardly different than he had been in college days. For a moment Stern felt again the adolescent admiration and fellowship he had felt so strongly then. Don't be stupid, he told himself angrily. This man had the money and the woman that had almost belonged to him.

Moving slowly, Stern deliciously savored the aroma of his triumph. On the table was the bottle. Clyde would be easy, unsuspecting, kindly.

It wouldn't be safe to marry Beryl right away, but there could never be any suspicion.

No need to hurry. For a moment he wanted to watch Curtis. He wondered what kind of pictures Clyde was seeing on the blank wall. Martian landscapes? The strange Ladonai? Too bad he hadn't stayed on Mars. Stern couldn't help having a friendly feeling for his old college chum, pity, too, for what must happen to him soon.

This was no way to kill anyone!

He was growing old and soft!

Nevertheless, Curtis did have a noble and striking face. Funny he had never noticed it before. It seemed to glow with an uncanny peace.

Unnoticed, the numbness crept from Stern's palm along his right arm, and a prickly sensation appeared in his right leg.

It was funny to read a person's thoughts like this. Love flowed from Curtis like the warm glow from a burning candle. A sort of halo had formed from the light above his head.

Symbolic.

From Curtis came wave after wave of love. He could feel it pulsating toward him, and he felt his own heart turn over, answer it. Yes, Curtis was noble.

Stern sank cross-legged on the floor beside Curtis and gazed at him. The prickly sensation had ascended from his leg up through his chest and to his neck. But it didn't matter. Now, for a last time, he could feel the spell of that perfect friendship—before the end.

What end? Why should there be any end to this eternal moment?

Curtis noticed him now. Those half-closed eyes were strangely penetrating. They looked him through.

"Well, Al," he said, "so you killed Schaughtowl?"

Stern looked at the kindly, godlike face and loved it.

Killed whom?

"Poor Al," Curtis said. He leaned over and laid his hand on the back of Stern's neck, fondling it much as one would a dog. "Poor old Al."

Stern's heart leaped in joy. This was ecstasy. It must be expressed. It demanded expression. If he had possessed a tail, he would have wagged it. Perhaps there was a word for that bliss. There was, and with immense satisfaction he spoke it.

"Gull Lup," he said.

—LUCIUS DANIEL

Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction April 1952. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed. Minor spelling and typographical errors have been corrected without note.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Martians Never Die, by Lucius Daniel

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MARTIANS NEVER DIE ***

***** This file should be named 29735-h.htm or 29735-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/2/9/7/3/29735/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Stephen Blundell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.net/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.net),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.net

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.